Visiting PR Off The Beaten Path

Visiting PR Off The Beaten Path

It is said that to truly get to know a place you visit, you must not only stick to tourist areas. Visiting PR and traveling off the beaten path will introduce you to a new Puerto Rico you haven’t seen. This particular side of Puerto Rico might not be the glossy one you see in brochures, but it is authentic. There are hidden gems to discover in nature, food, and most of all the Puerto Rican people. Most travelers agree that the people of Puerto Rico are the friendliest and most welcoming they have encountered. As Sebastian Modak from the New York Times recently discovered, you will find the up beat when you get off that beaten path. Today we feature the 52 Places Traveler and his recent Feb. 15th, 2019 article “Visiting Puerto Rico, and Finding the Up Beat”. The article features his journey of six days and his discoveries. Enjoy!

On a Monday night in San Juan, La Terraza de Bonanza is filled by lovers of plena and bomba music. Sebastian Modak/The New York Times

If this is a Monday night, it’s hard to imagine what Friday looks like. About 300 people are spilling out of a club onto Avenida Eduardo Conde in the Santurce district of San Juan. The space I’m in has limited seating, but the stools are empty anyway because everyone is standing. One window sells fluffy, fist-sized empanadillas and stacks of lightly salted tostones while another one hands over cans of Medalla beer at a furious pace. Everyone is here for bomba and plena, two distinct but closely linked Puerto Rican musical traditions that can trace their roots to the African slaves brought to the island starting in the 17th century.

The first set is all plena: A dozen men fill the stage, their fingers ricocheting off circular pandereta drums, providing a bedrock for the call-and-response vocal lines. The lyrics are largely improvised and often lewd and full of thinly veiled social and political commentary. There are repeated mentions of the venue we’re in, La Terraza de Bonanza, and calls to dance “la plena” and love “la isla.” Judging by the expressions on the faces of the people around me, the lyrics hold several inside jokes that fly right over my head.

After about an hour, there’s a 10-minute break and the set changes to bomba, an even older musical tradition (and a kind of cultural parent to plena) anchored by barrel-like drums. Women take center stage. A trio of vocalists face the drummers and a revolving cast of dancers leap, twirl, grin, shout and have me so transfixed that it’s a full 15 minutes before I realize I forgot to hit the record button on my camera.

I came to Puerto Rico, my first stop as this year’s 52 Places Traveler, hoping to see an island well on its way to recovery, a year and a half after Hurricane Maria. I knew I would see progress, especially when compared to the fresh devastation that my predecessor Jada Yuan saw just five months after the hurricane when she visited the island. What I didn’t expect to see were the omnipresent smiles, the sense of optimism shared by so many people I met, from pig roasters to young entrepreneurs, and from the meticulously manicured cobblestoned streets of Old San Juan to the roller-coaster hills in the center of the island.

[Born in the United States to a Colombian mother and an Indian father, Sebastian moved every few years during his childhood. Read more about our 52 Places Traveler.]

Throughout my six days on the island, a single sentence spoken to me by a 13-year-old in the ocean-hugging neighborhood of La Perla, just below Old San Juan, was on repeat in my mind: “La vida continúa,” or “Life goes on.”

The ensemble I saw at La Terraza, where it plays every Monday night, is more than a bar band. It’s a movement called Compartir de Plena, or Sharing Plena. Led by Alfredo Emerson and Axel Cotto, the group started five years ago in the northern coastal town of Cataño as a way to teach young people free of charge to play bomba and plena music. After Hurricane Maria hit, the group waited just two weeks before putting on a show in its hometown as a way to lift the spirits of a devastated population.

One week after that, Compartir de Plena were back at La Terraza de Bonanza, where a generator kept the beers cold and the microphones on for months. These days, the group sometimes streams the Terraza performances live on Instagram and Facebook, Mr. Emerson told me when I connected with him days after the performance. “It’s to bring happiness to people to see and hear our native music not just here in Puerto Rico, but also in other countries around the world,” he said.

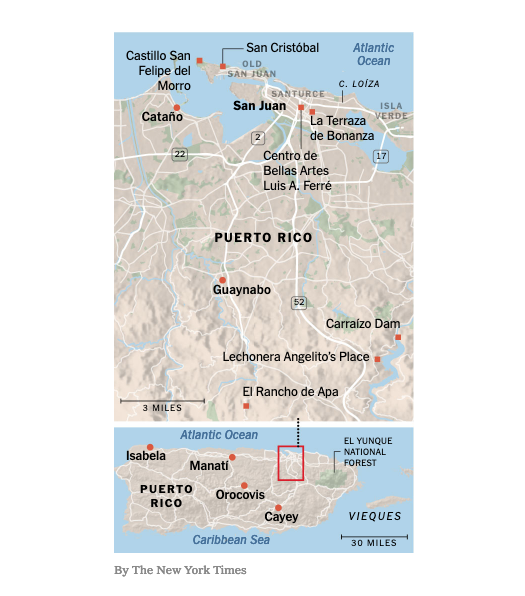

La Terraza de Bonanza was the first stop in my mission to explore the island of Puerto Rico beyond the regular tourism routes. I didn’t make it to a beach until my last full day. I never made it El Yunque, the giant National Forest that attracts hundreds of thousands of visitors a year. I didn’t have time to hop over to Vieques, the speck of land that sits off the main island’s east coast like a sideways teardrop. That’s not to say these aren’t attractions for good reasons, but I came wanting to see other parts of the island to see if those places had rebounded in the same way as the cruise ship ports and tour bus destinations. So I put the little time I had on the island largely into the hands of some young, energetic Puerto Ricans I met — one introducing me to another.

Loreana González Lazzarini, 34, is from Isabela, a town on the island’s northwestern coast. One day, she mapped out a trail of chinchorros (rural roadside restaurants) for me, stretching from the outskirts of San Juan to Orocovis, in the island’s center. The night before my road trip, speaking of the need for tourists to see the island beyond San Juan, Ms. González Lazzarini told me, “I want tourists to experience the people of Puerto Rico. Puerto Ricans’ main concern is always, ‘Are you having a good time?’”

Droves of tourists from around the world come to Old San Juan every year to take in its pastel-colored facades and historic sites, but few venture into the island’s interior.CreditSebastian Modak/The New York Times.

I spent the day alone, weaving through the winding, narrow roads that snake up and down jungle-covered hills into the interior. There were clear signs of the hurricane’s devastation. I saw the infamous blue tarps, still covering the tops of houses whose roofs had been blown off a year and a half ago. Rounding one corner I saw a pile of tree parts and, crossing right in front of it, a stray puppy dragging the beheaded carcass of an iguana: a poignant, if a little heavy-handed, symbol for the brutality of nature.

That same day, I saw the immense generosity that has carried the island through the hurricane and other crises over the past several years. I had made the mistake of trying to go on a “chinchorreo” on a Wednesday — for Puerto Ricans, it quickly became clear, that’s more of an activity for weekends. But one after another, the chinchorro owners whose places were closed until the weekend, rattled off recommendations for spots further down the road that might be open.

When I finally found a place for a late lunch — Roka Dura, an open-air restaurant at the top of a hill overlooking Orocovis — I ate a plate of country specialties: chicken chicharrón, fried till the skin cracked off the meat like an extra greasy potato chip; alcapurrias, fritters stuffed with mashed green plantains and ground meat; and longaniza, a Puerto Rican take on chorizo. After the meal, the server who had been making sure I liked everything, came over with a single sprig of fresh mint as a palate cleanser. “I know it’s organic because my neighbor grows it,” she said.

Castillo San Felipe del Morro, a 16th-century citadel on the northwestern tip of Old San Juan, reopened to visitors just two months after Hurricane Maria.CreditSebastian Modak/The New York Times

It took me a few days to realize it, but Ms. González Lazzarini’s own story is one that I heard, in some form or another, again and again during my time in Puerto Rico.

“I can’t think of my life without thinking of Hurricane Maria — it changed me,” she said. “Instead of B.C. and A.D., here it’s Before Maria and After Maria. B.M. and A.M.”

In Ms. González Lazzarini’s case, B.M. meant working at a major consulting firm in New York and then as a private consultant in Puerto Rico. A.M., her clients could not pay for consulting fees. Ms. González Lazzarini instead worked with a local nonprofit to distribute generators to businesses on Calle Loiza, a rapidly up-and-coming strip of bars and restaurants in Santurce. Then, she took a position with the recently established COR3, a local government agency working on reconstruction, recovery, and resilience following the hurricane.

“The hurricane took so much away from us, but it gave us something too,” Ms. González Lazzarini said. “It showed us how we can come together and organize as a people on our own.”

Some things I learned

-

Driving in the countryside is not as much of a white-knuckle experience as I had been led to believe. Still, you will find roads that are temporarily one lane, traffic lights that are out, and trucks in a rush. I found driving on the conservative side got me farther than trying to match the speed and daring of those who knew where they were going better than I did.

-

Power outages can still happen — and they can be unpredictable. My Airbnb, along with the rest of the neighborhood in Isla Verde, lost power for about six hours on one of the days I was there. Luckily, both power banks I’m traveling with were fully charged, so I could venture out for the duration, with full juice on my phone.

-

Uber is easy, affordable, and the best way to get around if you want to leave the rental car at the hotel. I often left mine behind when I was going into San Juan, or when I was going out at night to avoid parking headaches and driving at night.

For Xavier Pacheco, 40, a globally recognized chef, A.M. was about finally making the leap to what he considers his life’s work: a farm-to-table operation he’s starting with two chef-partners that will be, in his words, “our farm, with our animals, and a menu that comes from what we harvest.” He feels a magnetic tug away from the more established centers of tourism, on which he has relied. (He estimates that in his previous venture, the wildly successful Jaquita Baya, 70 percent of his customers were tourists).

“I’m refocusing on taking my product out of San Juan,” he told me, as I rode shotgun in his pickup truck past the Carraízo Dam, about 15 miles from Old San Juan. “The San Juan metro area is so saturated. There are a lot of places outside that area that are really cool — tourists should understand how much there is to see.” Put another way? “You have these people going to Señor Frogs and it’s like, ‘What’s the point?’ As a tourist, you could close your eyes in there and know your way to the bathroom.”

On my first day with Mr. Pacheco, I had one of two lunches at one of the “really cool” places he mentioned. I was hungry for lechón, the whole slow-roasted pig that is famous in the island’s interior, so we stopped at Lechonera Angelito’s Place. It is part of a strip that Mr. Pacheco calls “a mini Guavate,” referring to the section of the town of Cayey that’s become famous for the density of its lechoneras. This place is better, Mr. Pacheco promised. I can’t say how it compares with every other pig roast on the island, but it is hard to imagine anything more decadent than those chunks of meat, slick with melted fat, and layers of thick pig skin roasted to the consistency of hard candy.

After our meal, Mr. Pacheco introduced me to Junior Rivera, who has been running Angelito’s for 29 years. Mr. Rivera told me that he starts the roasting process at 1:30 a.m. every day and is in bed by 10 p.m. and that his recipe is basically a product of discovering what he likes. His A.M. story? “We were closed for two days. The day of the hurricane and the day after it, when the roads were closed,” he said.

On my second day with Mr. Pacheco, my last on the island, he took me to the northern central town of Manatí. On the way, we stopped for a breakfast of — what else? — more lechón, this time at the famous Rancho de Apa in Guaynabo. In Manatí we met with Efrén Robles who, with his wife, Angelie Martinez, run Los Frutos del Guacabo, an organic farm that runs on an on-demand model in collaboration with local chefs. Need more arugula? The farm will up production. Looking for grass-fed goat? Mr. Robles is in the middle of experimentation with cross-breeding to find the perfect balance between the longevity of the animal and the quality of meat.

As we walked, Mr. Robles picked soon-to-be garnishes the color of lipstick that tasted like black pepper and bright yellow bulbs that left a tingling sensation on my tongue. After the hurricane flattened the farm, it took Mr. Robles 177 days to get back on his feet, with some help from José Andrés’s World Central Kitchen. Now, he’s hoping to expand, potentially even into hospitality. When asked if, after the hurricane, he had ever considered taking his business or his expertise elsewhere it’s a quick “No.”

“I lived in Delaware for two years,” he told me as we took the five-minute drive from his farm to a pristine stretch of beach. “I’ll never forget the blizzard of ’96.”

Even Ms. González Lazzarini and Mr. Pacheco admitted I needed to spend at least half a day in Old San Juan, home to sprawling colonial-era fortresses like San Felipe del Morro and San Cristóbal. Beyond its Instagram-friendly beauty, the area, packed with cruise ship tours the day I went, is itself a symbol of post-hurricane, mid-debt crisis resilience.

Look at Old San Juan today and, apart from the political graffiti that speckles its outskirts, you would never imagine a hurricane that claimed the lives of almost 3,000 people had made landfall just a year and a half earlier. It’s in large part because of tourism: The brightly colored facades of Old San Juan were, somewhat controversially, a top priority in the rebuilding effort, given that they are the main source of tourist dollars on the island.

Tourist numbers are slowly creeping back to their pre-hurricane levels in Puerto Rico, even if most of those people are sticking to the same spots. But there’s at least one place that’s received a flood of newcomers: El Centro de Bellas Artes Luis A. Ferré. That’s because, for three weeks in January, the fine arts complex was playing host to “Hamilton,” with Lin-Manuel Miranda reprising his role as the title character for the first time in two and a half years. I went on a Thursday night during the last week of the show’s run. The crowd was electric even before the performance began, a steady din of excited whispers filling the space.

When Mr. Miranda stepped into the spotlight to the words “Alexander Hamilton,” the ensemble had to pause for a full two minutes to allow the standing ovation to pass. Every major number ended with raucous cheering. But different energy settled on the theater in the opening moments of “Hurricane,” in which Mr. Miranda sings, “In the eye of a hurricane, everything is quiet.” And it was. Even the applause at the end of the song seemed more subdued, more somber. By the end of the next number though, the crowd was smiling, whooping and loudly cheering once again.