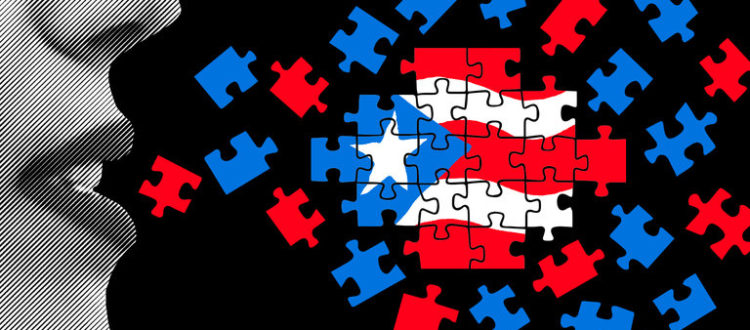

For the Love of Spanglish

For the Love of Spanglish

A different view on Spanglish:

AMHERST, Mass. — When I arrived at the San Juan airport in Puerto Rico recently, the first thing I heard was this exchange:

“Cómo estás, brother?”

“Muy cool!”

“Y la situación?”

“Ya tú sabes, stinky.”

(Or, roughly, “How are you?” “Really cool.” “How are things?” and “You know, stinky.”)

During that visit, evidence of Puerto Rico’s deep recession was everywhere to be seen: foreclosure signs, empty storefronts, closed public schools and a growing homeless population. Facing $123 billion in debt and pension obligations, the government is seeking bankruptcy relief in federal court.

Depending on whom you asked, either doomsday had finally arrived or this was just another hiccup in the long-suffering island’s history. It is estimated that between 2010 and 2015, 7 percent of the entire population moved to the mainland United States. Naturally, Puerto Ricans were sharply divided on how to resolve the crisis. But one thing united everyone: the eloquent Spanglish used to communicate the collective dismay.

Indeed, it takes any traveler no time to recognize that on the island such “code-switching” is truly democratic. No matter where one goes, Spanglish makes no distinction in terms of age, class or ethnicity. I heard it en la marketa (in the market), en la guagua (on the bus) and en el bloque (on the block). I heard Spanglish constantly on the radio in salsa, bomba, plena and reggaeton lyrics. And I saw it in the ubiquitous graffiti, which, more than in any other place I’ve been in the Spanish-speaking world, seem to favor double-entendres.

Nightlife in the Santurce neighborhood of San Juan, Puerto Rico. The island has developed a thriving version of Spanglish. Credit Victor J. Blue for The New York Times

Puerto Rican Spanglish didn’t just pop up out of the blue. It has been around since the Spanish-American War of 1898. Or, more concretely, since President Woodrow Wilson signed the Jones-Shafroth Act in 1917, when the island entered the colonial conundrum that keeps it upended. But in times of trouble, “la lengua misma te ayuda a bregar” (“the tongue itself helps you out”). I overheard this dialogue outside a restaurant:

“Vas al coffee break ahora?”

“No, porque si no doy overtime el boss me coge.”

“Careful y tómatelo suave.”

(“Are you going on a coffee break now?” “No, because if I don’t work overtime, my boss gets mad at me.” “Careful, take it easy.”)

Just as Puerto Rico Spanglish isn’t altogether new, the island isn’t the only ecosystem where this hybrid form of communication thrives. The United States-Mexican border is another fertile ground, although its Spanglish has a distinct vocabulary and different syntactic characteristics. Just as there are many varieties of Spanish in Hispanic countries — Argentine Spanish is different from Mexican, Colombian, Venezuelan, Cuban and so on — in the last 100 years or more, Spanglish has evolved sufficiently to establish an assortment of distinct, clearly defined types. Dominicanish, Cubonics, Tex-Mex and Chicano Spanglish in California need to be understood on their own terms.

Within those nationally defined groups, young people use Spanglish differently from their elders, just as immigrants use a type of Spanglish that is unlike the Spanglish spoken by second-generation Latinos. There is even a palpable difference between Puerto Rican Spanglish and Nuyorican, the Spanglish spoken by Puerto Ricans on the mainland. Each of these varieties is infused with a unique lexicon, accent and even style — “su propio revolú,” its own ruckus.

For a long time, purists have sought to stop the spread of Spanglish. They have described it as a pest, looking for ways to “correct” its speakers’ uncivilized parlance. For instance, in 1991 the Prince of Asturias Award, perhaps the most important cultural award in the Spanish-speaking world, was given to the people of Puerto Rico, “whose representative authorities, with exemplary decisiveness, have declared Spanish to be the only official language of the country.”

Likewise, the 2014 edition of the dictionary published by the Royal Spanish Academy, the watchdog of Spanish language usage, included 19,000 “Americanisms,” which are terms used by Latin American speakers of Spanish. A large percentage of those words are “Anglicisms” because they come from English. Common examples are “congresional” (congressional), “dron” (drone) and “nube informática” (iCloud).

What makes this edition of the dictionary a source of ridicule in Puerto Rico in particular is that just a few Anglicisms made it in, which means that the island’s parlance still remains largely beyond the purview of the academics who put together the lexicon. Buddy is “el broki.” And an invoice is “el cheque.” These simple terms aren’t registered in the prestigious lexicon, which means the joyful, exuberant Puerto Rican tongue was ignored.

It is time we stop this condescending approach to Spanglish. Puerto Ricans are proof of the durability of the phenomenon. In fact, we must see Spanglish as a new language. While it’s still not standardized, millions of speakers use it every day, creating their own syntactic rules. Looking down at them as barbarous speaks tons.

Curiously, while enjoying every sound San Juan had to offer, I kept on thinking of Yiddish, another “bastardized” tongue. Yiddish started as a mix of German and Hebrew, to which all sorts of other elements have been added over the centuries. At first it was spoken by women and children, so it was looked down upon by Talmudists and the educated elite as unworthy of serious consideration. But by the 19th century, Yiddish writers like Sholem Aleichem, author of “Tevye and His Daughters,” on which the Broadway musical “Fiddler on the Roof” was based, became best-selling authors. And in 1978, Isaac Bashevis Singer, among the most important writers of the 20th century, received the Nobel Prize in Literature for bringing the “universal human condition to life” in Yiddish.

Spanglish is transitioning from the oral to the written form, as novels, plays, movies, poetry, TV shows, translations, sermons and speeches are delivered in it. And it is already defining the future of the Americas. I will not be surprised if a Nobel is given in the next few decades to a Spanglish author whose oeuvre will need to be translated into Spanish and English to be fully understood by non-Spanglish speakers.

During my visit to San Juan, a performance artist assured me that U.F.O.s, if they ever land on the planet, would probably choose this island. He said it was unlikely that extraterrestrials would visit epicenters like Washington or other United States cities because they would get the executive order forbidding their entrance. In Puerto Rico, on the other hand, they will feel most welcome. They will also have a chance to appreciate the audacity of the population: “No hay money, time runs muy slow, but hey, la gente es super cool.”